And a River Went Out of Eden, 2018

TextImagesShocken Library, Jerusalem

Shocken Library, Jerusalem

The Library

Salman Schocken (1877-1959) was a businessman, owner of a chain of department stores in Germany, bibliophile, publisher, philanthropist, Zionist activist and art patron. In all he did, Schocken strove for holistic perfection; his deeply held belief in the importance of synchrony between form and function guided his myriad, diverse endeavors. Relentlessly attentive to the smallest of details in his projects, Schocken delved with equal zest into the typography of his department stores’ advertisements and the architecture and interiors of their buildings, which were planned by Erich Mendelsohn, an influential pioneer of 20th-century design and key figure in the history of modern architecture.

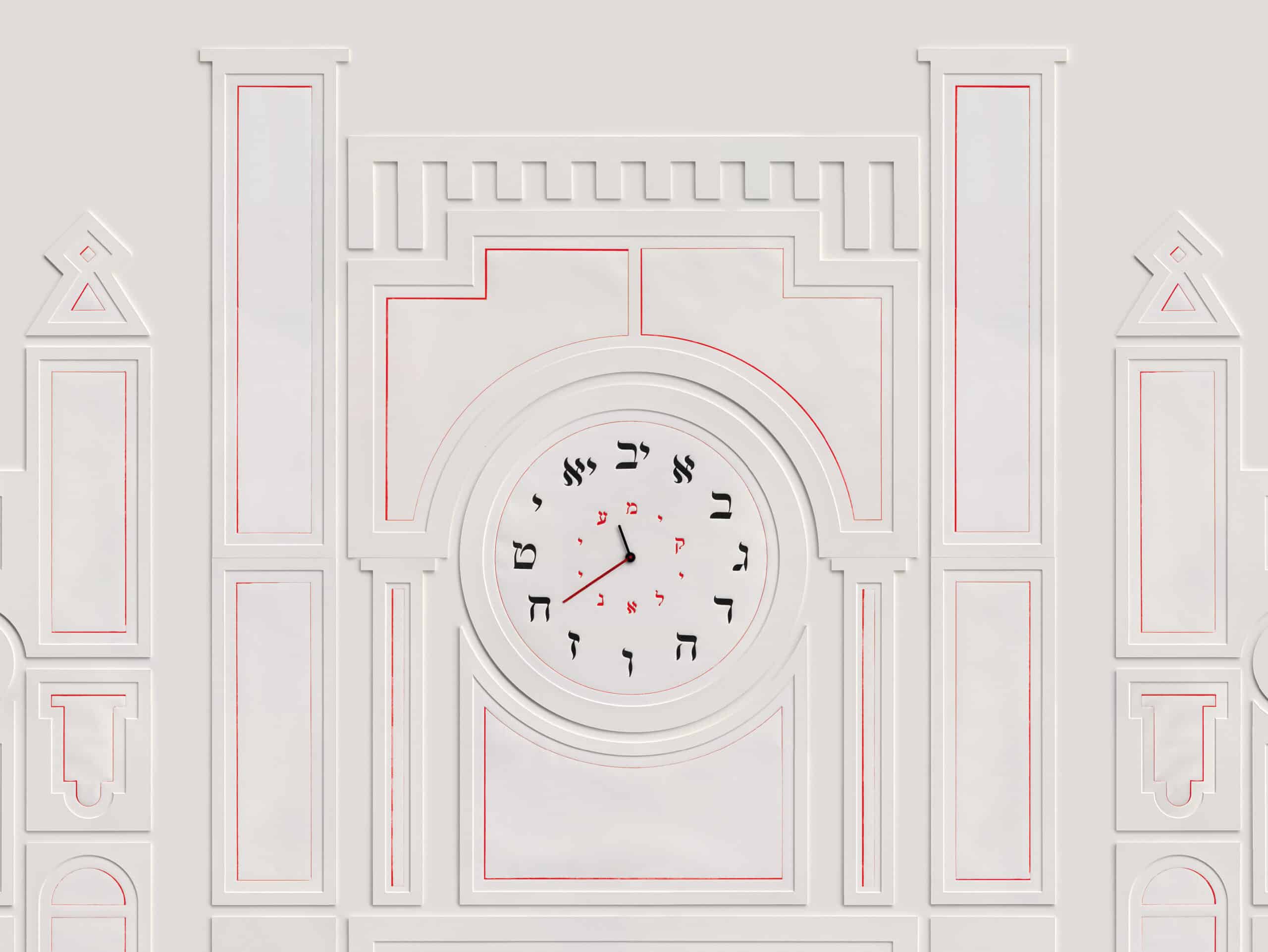

Schocken’s affiliation with the Spiritual Zionism of Martin Buber led him to search for ways in which the past could be generatively folded into the linear timeline, entwined with the present. Driven by his belief in the necessity of solid foundations, strong roots and a fertile context to the development and articulation of a new culture, Schocken worked to establish a vivifying, pulsing interrelation between historical time and his contemporary moment. In 1931, these ambitions led Schocken to found the Schocken Publishing House (Schocken Verlag) in Germany, dedicated to bringing to light masterpieces of Jewish culture, modern Hebrew poetry, and new editions of medieval Hebrew verse.

The initial staff of Schocken Publishing House included Lambert Schneider, Moshe Spitzer and Schocken himself. Schneider was an independent publisher who initiated a modern translation of the Hebrew Bible into German, a task for which he enlisted Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig. When the project was stalled by lack of funds, Schneider turned to Schocken for financial assistance. Having long planned to establish a press, Schocken proposed that Schneider join him in establishing Schocken Publishing House and bring the new Bible translation to completion there. Schneider served as manager of the publishing house until 1938, when Nazi Aryanization laws forced him to resign.

Moshe Spitzer tutored Schocken’s children in Hebrew and religious studies. His involvement in publishing began when he assisted Buber in the Bible translation project following Rosenzweig’s death in 1929. In 1933, two years after the establishment of Schocken Publishing House, the Schocken Library series (Bücherei des Schocken Verlag) was launched with Spitzer serving as the series’ managing editor and, at times, its book designer. Working as editor, typographer, designer, printer and typesetter, Spitzer time and again achieved extraordinary harmony between the books’ contents and their form.

Spitzer and Schneider, outstanding intellectuals and artisans who became specialists in all aspects of book production, needed to work swiftly and with agility, zigzagging between the numerous roles they assumed. When designs incorporated particularly complicated typography, the duo relied on Max Malte Müller, a professional typesetter and master printer.2

In its five short years of activity (1933-1938), the Schocken Library series grew to include ninety two volumes, reflecting the political moment’s acute sense of urgency and unrest, and evincing the rising demand for Jewish content. Schocken set nearly impossible deadlines, urging the publication of at least one book each month. All books in the Schocken Library series were printed in a consistent format: small, uniform, hardcover paper-bound editions, a different color for every book.3 These modest and restrained exteriors belie the dazzling cultural treasure trove that they contain.

The entire series, spread out like a rainbow on a bookshelf, was much admired by German Jews, for whom it provided precious gifts: a sense of belonging, context, identity. This culture-building process—the gathering and juxtaposing of diverse sources from different sites and disparate periods into a single coherent whole, and presenting them in a modern, accessible design—offered new perspectives on their history and their future. By constructing, or rediscovering, a coherent past and expanding cultural roots, the Library Series offered its readers firm footing from which to glimpse new horizons for a modern Judaism.

“The return to tradition as a core of the new—a recurrent element in Schocken’s thought and work—was expressed in the idea of the aestheticization of the everyday.”4 Customers who entered Schocken’s department stores roamed within Mendelsohn’s modern architectural wonders. The books they bought from Schocken Publishing House—with their clever, clear and timeless design—exposed them to a wealth of masterpieces. Without stepping outside the regular spheres of their everyday life, they were enriched by access to a shared culture of which they had no prior knowledge, for which they had a keen need.

* * *

In 1929, Erich Mendelsohn was given the opportunity to build his dream house in the Berlin suburb of Ropenhorn, on the banks of Stößensee Lake. Mendelsohn had waited many years for the chance to fully realize his vision without the interference of different factors (such as clients), who often demanded compromises. When the time arrived, Mendelsohn designed a house for him and his wife Louise, planning it to the most minute detail—from the position of the building on its site and its relation to the landscape, to the furniture, curtains, and even napkins and cutlery. Mendelsohn conceived the house as a comprehensive ensemble—a complete design system in which parts and whole are intrinsically linked—governed by principles of simplicity and functionality, and characterized by a caring attention to the qualities of raw materials and artisan craftsmanship. The house was designed in what would come to be known as the International Style and became an embodiment of Mendelsohn’s architectural language, as well as an important paragon of modern architecture. Sensing danger to the future of German Jews and struggling with the thought that he would have to leave his home, Mendelsohn had its every detail and angle documented in a series of wonderful photographs that were compiled and published as a book in 1932. A year later, the Mendelsohns were forced to abandon the house under the cover of darkness. He carried his house with him in this book, titled New House – New World (Neues Haus – Neue Welt).

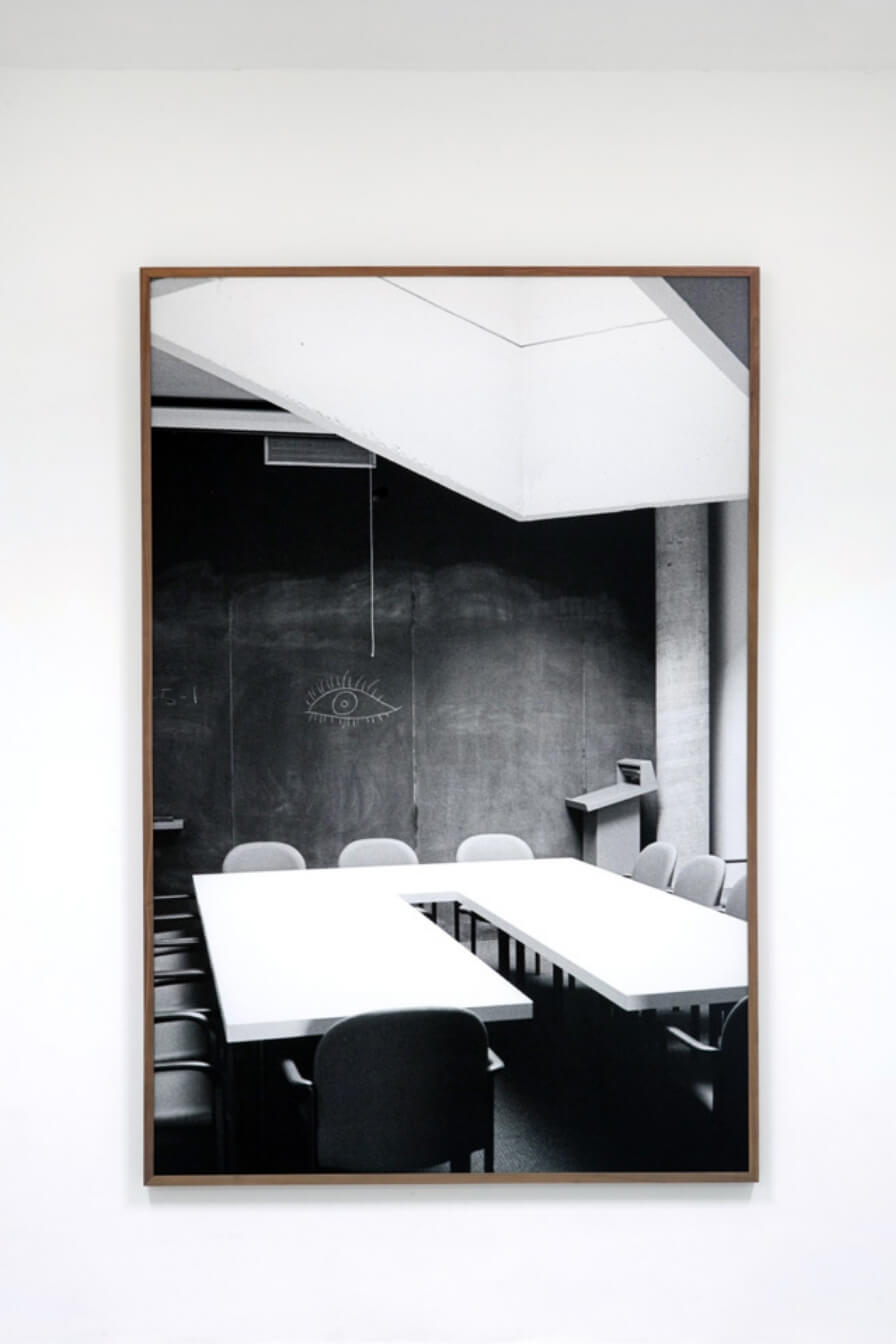

In 1934, Schocken and Mendelsohn both settled in Jerusalem. Schocken asked Mendelsohn to design both his house and a library that would house an institute for Jewish studies. In 1936, the library was established on 6 Balfour Street, where it remains to this day. Mendelsohn designed the library building and all its fittings, including bookcases, furniture, light fixtures, ventilation system and coat hangers. Like the books published by Schocken Publishing House, the reading hall in which this exhibition is presented was planned in a functional, simple and humble design, as an organic whole whose elements form a coherent system; a marvel of harmony between form and function.

On its long south-facing wall, the rectangular reading room is divided by a small semicircular balcony, characteristic of Mendelsohn’s designs. Seen from above, the footprint of the reading room evokes the shape of an open book, with the balcony serving as the book’s spine. A set of bookcases protected by glass doors stretches across the northern wall. Semicircular pillars with wood cladding stand between the bookcases. One pillar houses the ventilation system control panel, its semicircular profile echoing the curve of the balcony. Windows spanning the length and breadth of the space between the top of the bookcases and the ceiling are the room’s main source of illumination—a soft, filtered northern light that keeps the books protected. The three walls lit by direct sunlight are fitted with floor to ceiling bookcases enclosed behind wooden doors that offer the books maximal protection. Electrical sockets are installed within a marble baseboard that connects the wall and the floor; every detail of the space serves a precise purpose.

The design of the space is derived from the library’s program—it is primarily concerned with ensuring proper conditions for book storage and providing sufficient natural light for reading. One logic seems to guide everything, from detail to tectonic structure. This simple, shared formal logic—the lack of unnecessary elements, the play of light and shadow, the exposed raw materials—draws attention to the intriguing correlations between the building and the objects it houses, and between those objects and the proportions of the human body. This spatial experience is well-suited for a reading room; after all, the book itself, as a physical object, draws its form from the human body: we hold the two halves of an open book in our two palms, completing a circle; our spine and the book’s spine stand parallel. This posture opens us into a special state of being in which we can wander, contemplate, imagine, absorbed in our inner world. of an open book in our two palms, completing a circle; our spine and the book’s spine stand parallel. This posture opens us into a special state of being in which we can wander, contemplate, imagine, absorbed in our inner world.

The first book in the Schocken Library series, The Comforting of Israel (Die Tröstung Israels), and Mendelsohn’s New House, New World are roughly contemporaneous. The former includes German translations of consolation prophecies from the book of Isaiah. The latter presents the book as an architectural space and architectural space as mental space. Both books were published as Hitler rose to power. Both are reactions to cultural crisis, attempts at an escape from a dire reality; they are acts of bravery that grasp at art, at the creative act, as mooring for an imperiled belief in humanity. Not incidentally, both books conceive of the book as a home and of home as an idea that resides within us.

* * *

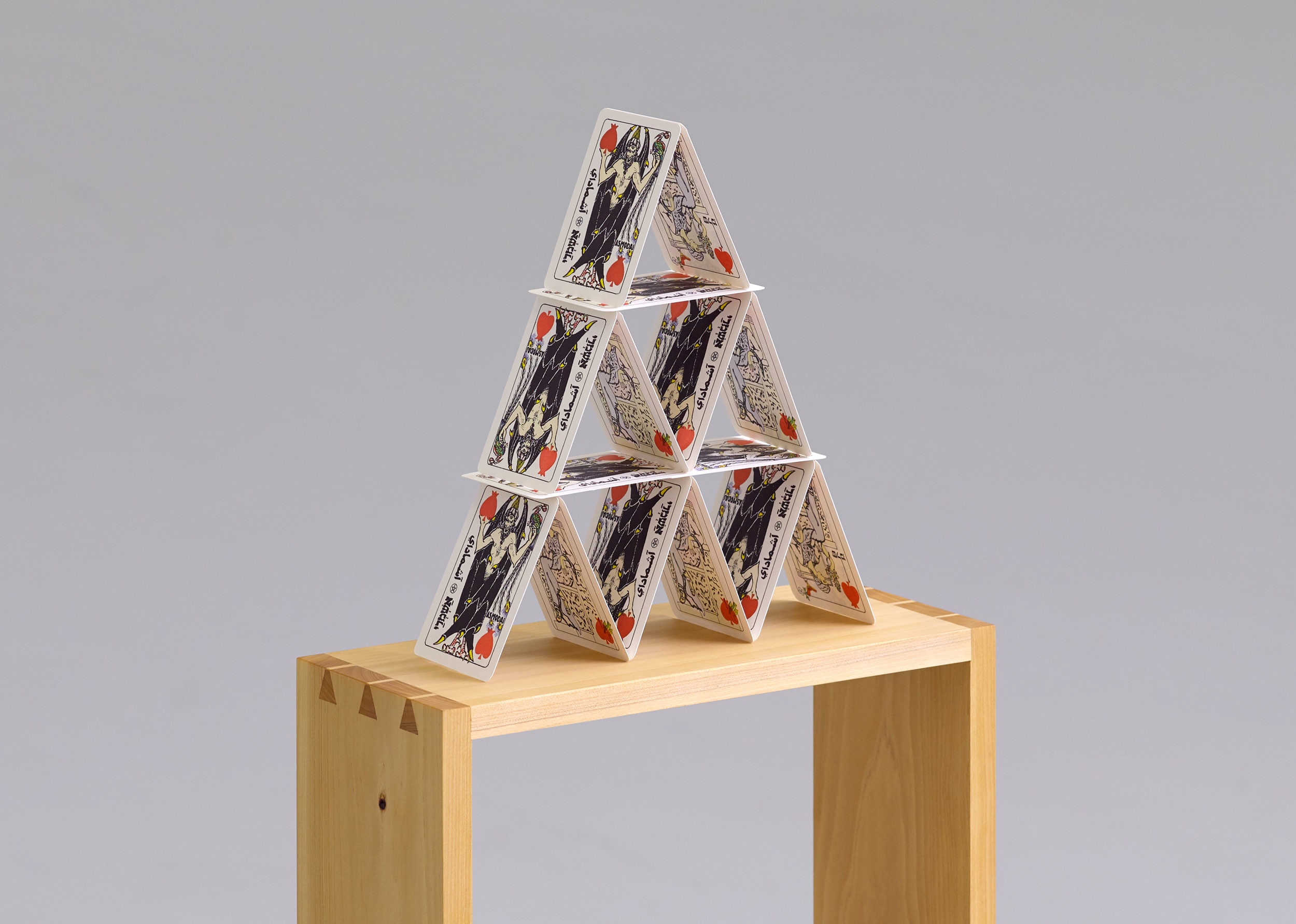

Schocken Library, and the interweaving actions and paths of the figures linked to it, are where I found a home to create my work. Through a long process of assembling, dismantling and reassembling, I discovered, over and over, new combinatorial possibilities, new trails to wander. The work First Six Panels consists of a sequence of images organized on the six display tables that Mendelsohn designed for the reading room. The images include reproductions from books that I have collected over the years and from books in the Schocken Library (The JTS-Schocken Institute for Jewish Research), as well as reproductions of my own works from different periods, and pictures of objects and artworks that I am fond of. Next to the six tables are two sculptures, Bird and Snail-Knife, that appear to me to be sort of crystallizations, formed from the liquid flow of images that streams around them, always in flux.

All the works and the elements that make up the exhibition are collected into yet another element of the project: the book you are holding in your hands. This book was printed in the format of the Schocken Library series and in its stylistic spirit, in order to look anew at this unique book series and, in so doing, fold time back on itself, closing a circle. Just as Schocken, Spitzer and Schneider worked together, inciting and inspiring each other as creative partners, I collaborated with Michael Gordon, this book’s designer. Between us was knit a tight mesh of conceptual exchange—a creative dialogue that disregarded conventional boundaries between creative fields and media, allowing us to freely share our expertise, interests and internal worlds. The photographs documenting the exhibition were shot to correspond to their layout within the pages of this book and the compositions of the images in the vitrines follow the book grid that Gordon designed for this publication—a grid that he arrived at by measuring and averaging the different layouts and compositional strategies in the original ninety two volumes of the Schocken Library series. The book presenting the exhibition functions as one of the works within it, an essential and inseparable part of the whole.